For many non-academic staffers at Harvard Law School, 24-year-old Rehan Staton from Maryland, U.S.A, is their unsung hero. But like most heroes, Staton had a rough beginning.

For many years, the young man and his family struggled with financial insecurity, illness and abandonment.

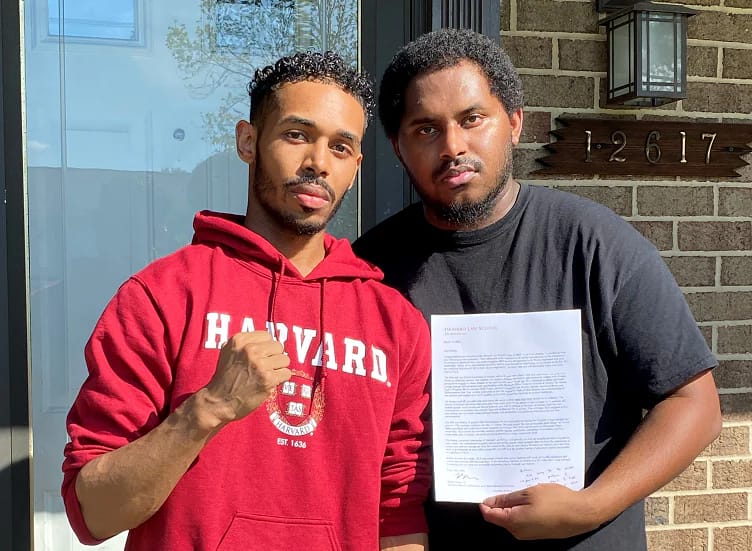

Rehan Staton and his brother Reggie worked for Bates Trucking & Trash Removal periodically for several years to help their father pay the bills.

“Things were pretty good until I was 8 years old,” said Staton, who grew up in Bowie, Md., and still lives there. “That’s when everything went south.”

“My mom abandoned my dad, my brother and I when she moved back to Sri Lanka,” said Staton.

“I was probably too young to notice some of the things that happened, but I know it was bad.”

After his mother left, Staton’s grades started slipping, he said.

“Things just kept falling on us,” Staton said. “My dad lost his job at one point and had to start working three jobs in order to provide for us. It got to the point where I barely got to see my father, and a lot of my childhood was very lonely.”

Although his father worked tirelessly to provide for his sons, the family of three struggled financially.

“There were often times without food on the table and no electricity in the house,” Staton recalled. “That was common throughout my childhood.”

At school, Staton remembers receiving no support. His teachers, he said, showed little faith in his academic abilities.

“One of them even called me handicapped,” Staton said.

Growing up, Staton said, he was “losing in everything.”

“I had no social life, home life was just horrible, and I hated school more than anything,” he said.

But there was one bright spot.

“I was really good at sports,” Staton said. His dream of becoming a professional boxer, he said, is what kept him going.

In 10th grade at Bowie High School, Staton hit a setback when he became ill with digestive problems and rotator-cuff injuries, quashing his hopes of pursuing a career as an athlete.

“I couldn’t go to the doctor because we didn’t have health insurance,” Staton said. “I was crushed.”

In 12th grade, Staton applied to college, knowing that there was little hope of being accepted given his low SAT score. “I got rejected by 100 percent of the schools that I applied to,” he said.

That’s when he went to work at Bates Trucking & Trash Removal. But to his surprise, it was his co-workers there who encouraged him to reapply to college.

“The other sanitation workers were the only people in my life who uplifted me and told me I could be somebody,” Staton said.

Brent Bates, whose father owns the trash company, helped Staton get in touch with a professor at Bowie State University, who assisted him with appealing his rejection from the school. Once Staton was ultimately accepted, his academic life finally began to flourish.

“I got a 4.0 GPA, I had a supportive community, and I became the president of organizations,” Staton said.

His brother, Reggie Staton, 27, was also enrolled at Bowie State University at the time but decided to drop out to work at the trash company so he could help financially support his brother and father.

“My brother took a job that people look down on, just so people could look up to me,” Rehan Staton said.

But for Staton’s brother, the sacrifice was well worth it, he said.

“My brother is everything to me. I would give up everything to see him succeed,” Reggie Staton said. “He’s my hero.”

Rehan Staton would dress in his neon-yellow uniform about 4 a.m. and head to Bates Trucking & Trash Removal in Bladensburg, Md.

He spent his mornings hauling trash and cleaning dumpsters, then went to class at the University of Maryland.

When there was no time to shower between work and class, he would sit at the back of the lecture hall to avoid inevitable glares and judgment from his peers, he said.

Although it wasn’t Staton’s first time being a sanitation worker, he hopes it is his last: The 24-year-old Maryland man was recently accepted to Harvard Law School.

The road to receiving the acceptance letter was long and bumpy, he said.

After two years at Bowie State, Staton transferred to the University of Maryland to complete the remainder of his undergraduate degree.

Although he was succeeding as a student, Staton continued to face personal hardships. In his second semester at the University of Maryland, his father suffered a stroke.

Staton started working at the trash company once again to help pay his father’s medical bills while staying in school.

Balancing work and college was not easy, Staton said, especially because he wanted to apply to law school and needed to maintain his grades.

“We all took losses and made sacrifices to take care of each other,” Staton said of his family.

Staton’s cousin, Dominic Willis, 24, agrees. “Rehan’s desire to provide for his family always overtakes whatever issue he is battling.”

After he graduated from the University of Maryland in December 2018 (he was chosen to be student commencement speaker), Staton took a job at the Robert Bobb Group, a national consulting firm in the District.

Despite continuing to battle stomach issues after graduation, Staton thrived in his role as an analyst.

“For Rehan, the sky is truly the limit,” said Patrick Bobb, 33, chief operating officer at Robert Bobb Group.

“He is unbreakable. Whatever Rehan chooses to do in his legal career and beyond, he will definitely achieve.”

While working full time, Staton took the LSAT and applied to law school. He received his acceptance letters in March.

When Rehan got into Harvard, “I felt at that moment, my brother made every sacrifice worth it,” said Reggie Staton.

“He did what he said he was going to do, and that was to get into a top law school.”

Staton was also accepted to the law schools at Columbia University, the University of Pennsylvania, the University of Southern California and Pepperdine Law. He was wait-listed at Georgetown University, New York University, Berkeley and UCLA.

He is now partnering with Brad Barbay LSAT Prep to offer free LSAT tutoring to students.

When his story went public, a cascade of financial support followed, including a GoFundMe account from well wishers and financial support from actor and filmmaker Tyler Perry, who covered Staton’s tuition.

“He had a tough upbringing but worked hard at a tireless job to eventually reach his goal,” Perry said in an email to The Post. “He deserved being able to attend Harvard the last few years without having any future financial concerns.”

Three years later, Staton — who is to graduate in May — is focused on giving something back, specifically to the law school’s support staffers — including custodians, electricians and food service workers. He felt they were not getting the recognition they deserved for helping the school to run smoothly.

When Staton arrived on campus at Harvard last fall after completing his first year virtually, he engaged with students and faculty members — but he made a special effort with custodians, cafeteria workers and security staffers. They felt like family, he said.

“We text, we hug when we see each other, I call them aunts and uncles,” Staton said. “I have felt very safe, taken care of and loved, specifically because of the bonds that I have with my support staff.”

“When I see them, I see me,” he continued. “I view them as my equal. They are just my peers.”

In February 2022, one week after the custodian told him that students would prefer to look at a wall than talk to her, Staton used his savings from a summer job as an associate at a D.C. law office to purchase 100 Amazon gift cards to distribute to support staffers around the school. He included a handwritten note with each, expressing his gratitude to the worker.

In addition to handing out the cards, he asked how their lives on campus could be improved. Many told him they did not feel seen by students.

Staton made it his mission to change that. He started the Reciprocity Effect, a nonprofit organization to support what he calls the “unsung heroes” who work behind the scenes. The organization offers need-based grants and also recognizes workers.

He told Brent Bates, the assistant operations manager at his former employer Bates Trucking & Trash Removal in Bladensburg, Md., about his idea, and Bates was eager to join. He became the co-founder of the Reciprocity Effect.

“I know what it feels like to be in a position where people would rather act like you don’t exist,” said Bates, 31, who has known Staton for about 10 years and encouraged him to go to college.

Bates and his father, who owns the sanitation company, donated $50,000 toward the organization. Supporting others, Bates said, is “something we pride ourselves on.”

Staton, whose family still lives in Bowie, Md., said he was humbled and overjoyed by their response.

“I’ve never seen something come full circle like this,” Staton said. “The same sanitation company that changed my life, I came back to them, and they said, ‘We’ll be right there with you.’”

Other students were keen to get involved in the initiative, too. Among them was Lla Anderson, a Floridian in her first year at the law school.

“Every day, I talk to support staff. We joke, we laugh, we confide in each other,” said Anderson, 24. “They’re my friends.”

In fact, more than once, support staffers bought groceries for her when she struggled to afford them herself. When a staff member found out she would be spending a holiday alone, he invited her to celebrate with his family.

Staton and Bates organized a “thank you” card drive in November, enlisting more than 250 students to write messages of gratitude to support staffers at the school. The cards were distributed along with Amazon gift cards.

“People were truly inspired to start taking things to another level,” Staton said.

In the months that followed, he and a small team of students at the school have been fundraising and have collected more than $70,000 in donations, he said.

For the official launch of the Reciprocity Effect on Monday, they organized an awards banquet at Harvard Law School, and 30 support staffers received customized trophies honoring their work, as well as $100 Amazon gift cards.

Students and staffers voted to determine the winners of the various awards, and more than 160 people attended the event.

Brione Merchant, who has worked in cafeterias on campus for 16 years, was one of the awardees. He and his colleagues were overcome with emotion, he said.

“There’s a lot of prideful people that work at this university that do things that a lot of people wouldn’t have pride in doing,” said Merchant, 43. “To acknowledge those people is very important.”

The Reciprocity Effect, he said, already has made a difference.

“Since Monday, everybody has been walking around just a little bit taller, and that’s just a beautiful thing to see and be a part of,” Merchant said.

The event offered a rare opportunity for support staffers to be in the spotlight and for students to cheer them on.

“They weren’t serving; they were being served,” Anderson said. “To see that, that was incredible. It felt amazing, and it felt like it was just the beginning.”

Staton — who has secured a job for after graduation at a law firm in New York City — hopes to expand the initiative beyond Harvard to educational institutions across the country. He wants support staffers everywhere to feel recognized.

Culled from Washington Post