Former United States President, Donald Trump, had foreign bank accounts in China, the UK, Ireland and St Maarten during his presidency.

In his first year in the White House, he paid more foreign tax than US tax, his tax returns have shown.

Democrats in Congress released thousands of pages of former President Donald Trump’s tax returns on Friday.

It provided the most detailed picture to date of his finances over a six-year period, including his time in the White House, when he fought to keep the information private in a break with decades of precedent.

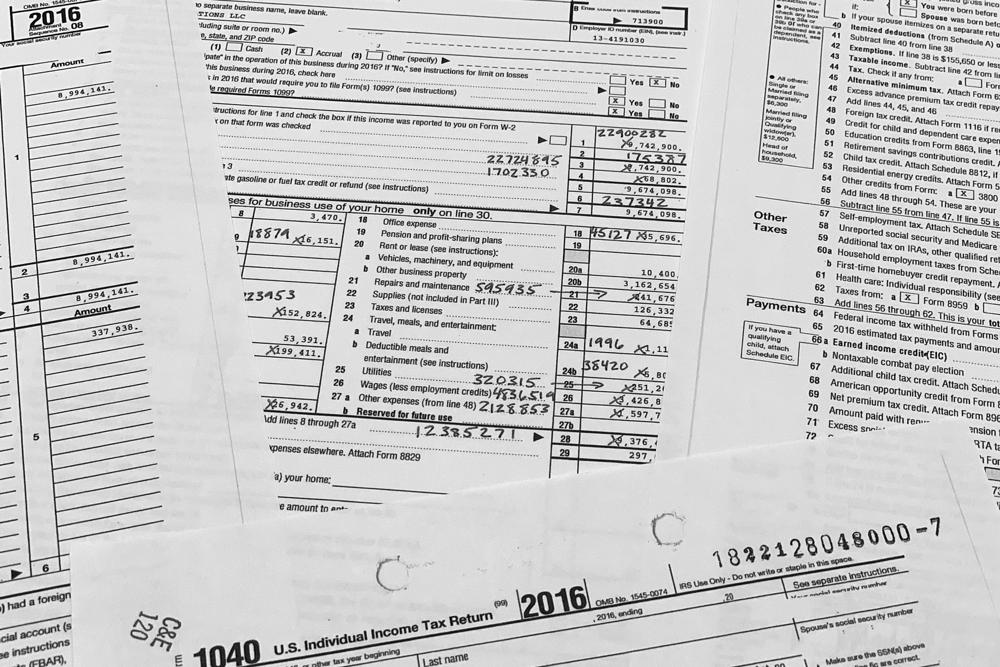

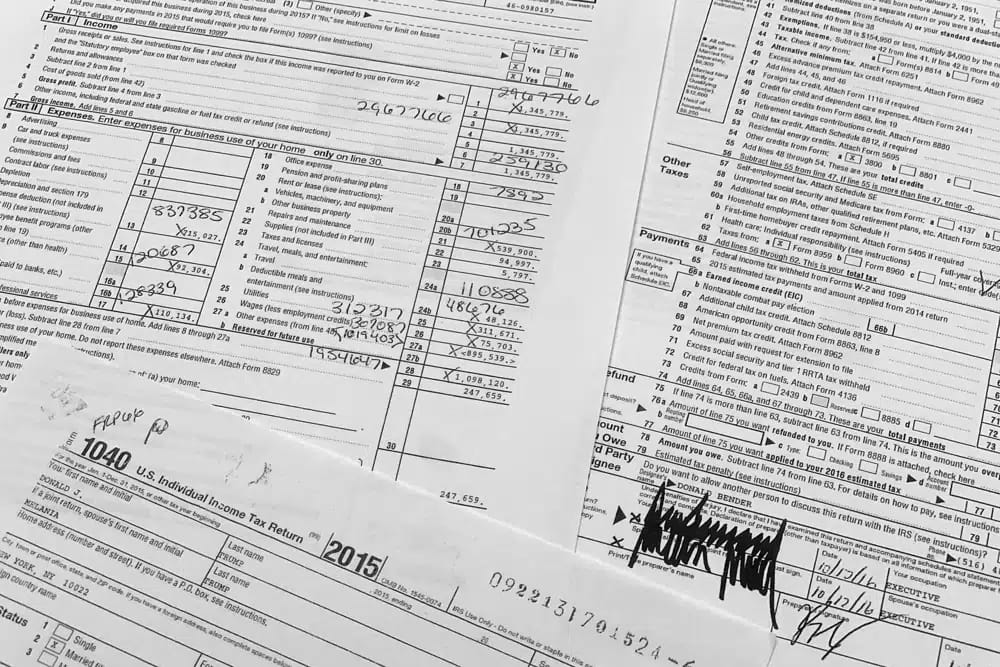

The documents include individual returns from Trump and his wife, Melania, along with Trump’s business entities from 2015-2020.

They show how Trump used the tax code to lower his tax obligation and reveal details about foreign accounts, charitable contributions and the performance of some of his highest-profile business ventures, which had largely remained shielded from public scrutiny.

The disclosure marks the culmination of a years long legal fight that has played out everywhere from the presidential campaign to Congress and the Supreme Court as Trump persistently rejected efforts to share details about his financial history — counter to the practice of transparency followed by all his predecessors in the post-Watergate era.

The records release comes just days before Republicans retake control of the House and weeks after Trump announced another campaign for the White House.

The records show how Trump limited his tax liability by offsetting his income against corporate losses as well as millions of dollars in business expenses, asset depreciation and other deductions.

While Trump paid $641,931 in federal income taxes in 2015, the year he began his campaign for president, he paid just $750 in 2016 and 2017, according to a report released last week by Congress’ nonpartisan Joint Committee on Taxation.

According to the tax returns released by the House Ways and Means Committee on Friday, Trump’s foreign financial interests were still quite strong.

The ex-US president put his company in a blind trust controlled by his adult children upon taking the presidency in 2017.

He paid nearly $1 million in 2018, but only $133,445 in 2019 and nothing in 2020, the year he unsuccessfully sought reelection.

Trump’s tax returns were made public after years of legal battles between him and the Democrat controlled House of representatives, all of which he lost, even at the Supreme court.

The records also detail Trump’s foreign holdings.

Trump, according to the filings, reported having bank accounts in China, Ireland and the United Kingdom in 2015 through 2017, even as he was commander in chief. Starting in 2018, however, he only reported an account in the U.K.

The returns also show that Trump claimed foreign tax credits for taxes he paid on various business ventures around the world, including licensing arrangements for use of his name on development projects and his golf courses in Scotland and Ireland.

In several years, Trump appears to have paid more in foreign taxes than he did in net U.S. federal income taxes, with income reported in countries including Azerbaijan, China, India, Indonesia, Panama, the Philippines, St. Martin, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates.

The documents also show that Trump’s charitable donations often represented only a sliver of his income. In 2020, the year the coronavirus ravaged the economy, Trump reported no charitable donations at all.

In 2018 and 2019, he reported writing checks for about $500,000 in donations. In earlier years the numbers were higher — $1.8 million in 2017 and $1.1 million in 2016.

It’s unclear whether the reported sums included Trump’s $400,000 annual presidential salary, which he had said, as a candidate, that he would forgo and which he claimed he donated to various federal departments.

Jeff Hoopes, an accounting professor at the University of North Carolina’s Kenan-Flagler Business School, described Trump’s returns as “large and complicated” with “hundreds of entities scattered all over the globe.”

He noted that many of those entities are slightly unprofitable, which he described as “pretty magical as far as the tax code.”

“It’s hard to know if someone’s really bad at business or really good at tax planning, because they both look like the same thing,” he said.